Exception handling can make or break your application. If exceptions aren’t handled properly, your API could leak sensitive stack traces, return inconsistent error formats, or worse — crash entirely. I’ve seen production systems go down because a single unhandled null reference propagated through the entire request pipeline.

In this guide, we’ll cover everything you need to know about global exception handling in ASP.NET Core — from the old try-catch approach to the modern IExceptionHandler introduced in .NET 8, all the way to the new .NET 10 features like SuppressDiagnosticsCallback. By the end, you’ll have a production-ready exception handling setup that’s clean, maintainable, and follows best practices.

TL;DR - Which Approach Should You Use?

If you’re in a hurry, here’s the quick comparison:

| Approach | When to Use | .NET Version |

|---|---|---|

| Try-Catch Blocks | Never for global handling. Only for specific, localized error recovery. | All |

UseExceptionHandler Lambda | Quick prototypes or simple APIs with minimal error handling needs. | All |

| Custom Middleware | Legacy projects on .NET 7 or earlier. Migrate to IExceptionHandler when possible. | All |

IExceptionHandler | Production applications. This is the recommended approach. | .NET 8+ |

Bottom line: If you’re on .NET 8 or later, use IExceptionHandler. It’s cleaner, more testable, and gives you the flexibility to handle different exception types exactly how you want.

What Are Exceptions in .NET?

Before diving into handling mechanisms, let’s quickly cover the basics. Exceptions in .NET are objects that inherit from System.Exception and represent errors that occur during program execution. When something goes wrong, you throw an exception, and it propagates up the call stack until something catches it.

Common exceptions you’ll encounter:

NullReferenceException— The classic “object reference not set” errorArgumentNullException— When a required argument is nullInvalidOperationException— When an operation isn’t valid for the current stateKeyNotFoundException— When a dictionary lookup failsHttpRequestException— When an HTTP call fails

The goal of global exception handling is to catch any unhandled exceptions before they reach the client, log them properly, and return a consistent, safe error response.

The Evolution of Exception Handling in ASP.NET Core

ASP.NET Core has evolved significantly in how it handles exceptions. Let’s walk through each approach so you understand why IExceptionHandler is now the recommended solution.

1. Try-Catch Blocks (The Naive Approach)

This is what most developers start with:

[HttpGet("{id}")]public IActionResult GetProduct(int id){ try { var product = _productService.GetById(id); return Ok(product); } catch (Exception ex) { _logger.LogError(ex, "Error fetching product {ProductId}", id); return StatusCode(500, "An error occurred"); }}This works, but imagine having to write this in every single endpoint. Your codebase becomes cluttered with repetitive try-catch blocks, and there’s no guarantee that every developer on the team will handle errors consistently.

Verdict: Use try-catch only for specific scenarios where you need localized error recovery — not for global exception handling.

2. Built-in UseExceptionHandler Middleware

ASP.NET Core provides a built-in middleware that catches exceptions from the pipeline:

app.UseExceptionHandler(options =>{ options.Run(async context => { context.Response.StatusCode = StatusCodes.Status500InternalServerError; context.Response.ContentType = "application/json";

var exceptionFeature = context.Features.Get<IExceptionHandlerFeature>(); if (exceptionFeature is not null) { var error = new { message = "An unexpected error occurred" }; await context.Response.WriteAsJsonAsync(error); } });});Let me break this down:

- Line 1:

UseExceptionHandleradds the exception handling middleware to the pipeline. Any unhandled exception from downstream middleware or endpoints will be caught here. - Line 3:

options.Runregisters a terminal middleware — it handles the request and doesn’t call the next middleware. - Lines 5-6: We set the HTTP status code to 500 and content type to JSON. This ensures the client knows what kind of response to expect.

- Line 8:

IExceptionHandlerFeaturegives us access to the original exception. ASP.NET Core stores exception details in this feature when an error occurs. - Lines 11-12: We create an anonymous object and serialize it as JSON. Simple, but not ideal for production.

This is better — all exceptions flow through one place. But it’s limited. You’re writing inline code in Program.cs, which isn’t great for testing or complex logic. Plus, handling different exception types becomes messy fast.

3. Custom Middleware (Pre-.NET 8 Approach)

Before .NET 8, the cleanest approach was building custom middleware:

public class ExceptionHandlingMiddleware(RequestDelegate next, ILogger<ExceptionHandlingMiddleware> logger){ public async Task InvokeAsync(HttpContext context) { try { await next(context); } catch (Exception ex) { logger.LogError(ex, "Unhandled exception occurred"); await HandleExceptionAsync(context, ex); } }

private static async Task HandleExceptionAsync(HttpContext context, Exception exception) { context.Response.ContentType = "application/json"; context.Response.StatusCode = exception switch { KeyNotFoundException => StatusCodes.Status404NotFound, ArgumentException => StatusCodes.Status400BadRequest, _ => StatusCodes.Status500InternalServerError };

var problemDetails = new ProblemDetails { Status = context.Response.StatusCode, Title = "An error occurred", Detail = exception.Message };

await context.Response.WriteAsJsonAsync(problemDetails); }}Here’s what’s happening:

- Line 1: We’re using a primary constructor (C# 12 feature) to inject

RequestDelegateandILogger. TheRequestDelegate nextrepresents the next middleware in the pipeline. - Lines 5-7: The try block wraps the call to

next(context). This means any exception thrown by downstream middleware or endpoints gets caught here. - Lines 9-12: When an exception occurs, we log it and pass it to our handling method.

- Lines 19-24: This is where it gets interesting. We use a switch expression to map exception types to HTTP status codes.

KeyNotFoundExceptionbecomes 404,ArgumentExceptionbecomes 400, and everything else defaults to 500. - Lines 26-31: We build a

ProblemDetailsobject — this is the RFC 7807 standard for error responses. It gives clients a consistent structure to parse. - Line 33: Finally, we serialize the problem details as JSON and write it to the response.

Register it in Program.cs:

app.UseMiddleware<ExceptionHandlingMiddleware>();This works well and was the standard for years. But .NET 8 introduced something better.

4. IExceptionHandler (The Modern Way - .NET 8+)

IExceptionHandler is an interface that lets you handle exceptions in a clean, testable, and modular way. It plugs directly into ASP.NET Core’s built-in exception handling middleware — so when Microsoft improves that middleware, you get the benefits for free.

Here’s why it’s superior:

- Dependency injection — Your handlers are registered in DI, so you can inject services

- Testable — Easy to unit test without spinning up the entire HTTP pipeline

- Chainable — Register multiple handlers for different exception types

- Framework-integrated — Uses the same middleware Microsoft maintains

Let’s dive deep into how to use it.

Creating Custom Exception Classes

Before implementing the handler, let’s set up proper custom exceptions. This makes your code more readable and your error handling more precise.

Create a base exception class:

public abstract class AppException : Exception{ public HttpStatusCode StatusCode { get; }

protected AppException(string message, HttpStatusCode statusCode = HttpStatusCode.InternalServerError) : base(message) { StatusCode = statusCode; }}Let me explain why this design matters:

- Line 1: The class is

abstract— you can’t instantiate it directly. This forces developers to create specific exception types likeNotFoundExceptioninstead of throwing genericAppException. - Line 3: We store the

HttpStatusCodeas a property. This is the key insight — the exception knows what HTTP status it should return. Your handler doesn’t need complex switch statements to figure this out. - Lines 5-8: The constructor takes a message and an optional status code (defaulting to 500). We pass the message to the base

Exceptionclass and store the status code.

Now create specific exceptions:

public sealed class NotFoundException : AppException{ public NotFoundException(string resourceName, object key) : base($"{resourceName} with identifier '{key}' was not found.", HttpStatusCode.NotFound) { }}

public sealed class BadRequestException : AppException{ public BadRequestException(string message) : base(message, HttpStatusCode.BadRequest) { }}

public sealed class ConflictException : AppException{ public ConflictException(string message) : base(message, HttpStatusCode.Conflict) { }}

public sealed class ValidationException : AppException{ public IDictionary<string, string[]> Errors { get; }

public ValidationException(IDictionary<string, string[]> errors) : base("One or more validation errors occurred.", HttpStatusCode.BadRequest) { Errors = errors; }

public ValidationException(string field, string error) : base("One or more validation errors occurred.", HttpStatusCode.BadRequest) { Errors = new Dictionary<string, string[]> { { field, [error] } }; }}Notice a few things:

- Line 1: Each exception is

sealed— no further inheritance needed. This is a small optimization and makes the intent clear. - Lines 3-4:

NotFoundExceptiontakesresourceNameandkeyparameters. This creates a descriptive message like “Product with identifier ‘123’ was not found.” Anyone reading logs instantly knows what went wrong and for which resource. - Lines 9-12:

BadRequestExceptionis simpler — it just takes a message and maps to 400 Bad Request. - Lines 17-20:

ConflictExceptionmaps to 409 Conflict — useful for duplicate entries or concurrent modification errors. - Lines 23-38:

ValidationExceptionis special — it carries field-level errors in a dictionary. This works seamlessly withValidationProblemDetailsfor form validation scenarios. The two constructors allow either a full dictionary of errors or a single field/error pair for convenience.

Now you can throw meaningful exceptions from your services:

public Product GetById(Guid id){ var product = _repository.Find(id); if (product is null) { throw new NotFoundException("Product", id); } return product;}Get the point? The exception carries all the context needed for proper error handling downstream.

Implementing IExceptionHandler in .NET 10

Here’s a production-ready implementation that uses IProblemDetailsService for RFC 9457-compliant responses:

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Diagnostics;using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

public sealed class GlobalExceptionHandler( ILogger<GlobalExceptionHandler> logger, IProblemDetailsService problemDetailsService) : IExceptionHandler{ public async ValueTask<bool> TryHandleAsync( HttpContext httpContext, Exception exception, CancellationToken cancellationToken) { logger.LogError(exception, "Unhandled exception occurred. TraceId: {TraceId}", httpContext.TraceIdentifier);

var (statusCode, title) = MapException(exception);

httpContext.Response.StatusCode = statusCode;

var problemDetails = new ProblemDetails { Status = statusCode, Title = title, Type = GetProblemType(statusCode), Instance = httpContext.Request.Path, Detail = GetSafeErrorMessage(exception, httpContext) };

problemDetails.Extensions["traceId"] = httpContext.TraceIdentifier; problemDetails.Extensions["timestamp"] = DateTime.UtcNow;

return await problemDetailsService.TryWriteAsync(new ProblemDetailsContext { HttpContext = httpContext, ProblemDetails = problemDetails }); }

private static (int StatusCode, string Title) MapException(Exception exception) => exception switch { AppException appEx => ((int)appEx.StatusCode, appEx.Message), ArgumentNullException => (StatusCodes.Status400BadRequest, "Invalid argument provided"), ArgumentException => (StatusCodes.Status400BadRequest, "Invalid argument provided"), UnauthorizedAccessException => (StatusCodes.Status401Unauthorized, "Unauthorized"), _ => (StatusCodes.Status500InternalServerError, "An unexpected error occurred") };

private static string GetProblemType(int statusCode) => statusCode switch { 400 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.1", 401 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.2", 403 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.4", 404 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.5", 409 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.10", _ => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.6.1" };

private static string? GetSafeErrorMessage(Exception exception, HttpContext context) { // Only expose details in development var env = context.RequestServices.GetRequiredService<IHostEnvironment>(); if (env.IsDevelopment()) { return exception.Message; }

// In production, only expose messages from our own exceptions return exception is AppException ? exception.Message : null; }}This is the heart of our exception handling. Let me walk you through each part:

Constructor and Dependencies (Lines 4-6)

public sealed class GlobalExceptionHandler( ILogger<GlobalExceptionHandler> logger, IProblemDetailsService problemDetailsService) : IExceptionHandlerWe inject two services:

ILogger<GlobalExceptionHandler>— For logging exceptions with proper categorizationIProblemDetailsService— ASP.NET Core’s built-in service for writing RFC 9457-compliant responses. This handles content negotiation, serialization, and ensures consistent formatting.

The TryHandleAsync Method (Lines 8-36)

This is the only method required by IExceptionHandler. It receives three parameters:

HttpContext httpContext— The current request context, giving us access to the response, request path, and servicesException exception— The actual exception that was thrownCancellationToken cancellationToken— For handling request cancellation

Lines 13-14: First, we log the exception. Notice we include httpContext.TraceIdentifier — this is crucial for correlating logs with specific requests. When a user reports an error, you can search your logs by this trace ID.

Line 16: We call MapException to determine the appropriate HTTP status code and title. This uses pattern matching to handle different exception types elegantly.

Line 18: We set the response status code. This must happen before writing the response body.

Lines 20-27: We build the ProblemDetails object:

Status— The HTTP status code (400, 404, 500, etc.)Title— A short, human-readable summaryType— A URI reference to documentation about this error type (RFC 9110 references)Instance— The specific request path that caused the errorDetail— Additional information (only in development or for safe exceptions)

Lines 29-30: We add custom extensions to the problem details. traceId helps with debugging, and timestamp records when the error occurred. These appear in the JSON response.

Lines 32-36: Instead of manually serializing JSON, we use IProblemDetailsService.TryWriteAsync. This service:

- Handles content negotiation (respects

Acceptheaders) - Applies any global customizations from

AddProblemDetails() - Returns

trueif it successfully wrote the response,falseotherwise

Exception Mapping (Lines 39-46)

private static (int StatusCode, string Title) MapException(Exception exception) => exception switch{ AppException appEx => ((int)appEx.StatusCode, appEx.Message), ArgumentNullException => (StatusCodes.Status400BadRequest, "Invalid argument provided"), // ...};This switch expression maps exceptions to HTTP responses:

AppException(our custom base) — Uses the status code embedded in the exception itselfArgumentNullExceptionandArgumentException— Map to 400 Bad RequestUnauthorizedAccessException— Maps to 401 Unauthorized- Everything else — Defaults to 500 Internal Server Error

Safe Error Messages (Lines 58-69)

private static string? GetSafeErrorMessage(Exception exception, HttpContext context){ var env = context.RequestServices.GetRequiredService<IHostEnvironment>(); if (env.IsDevelopment()) { return exception.Message; } return exception is AppException ? exception.Message : null;}This is a security-critical method. In development, we show the full exception message for debugging. In production:

- For

AppExceptiontypes (our own exceptions), we show the message — we control these and know they’re safe - For system exceptions, we return

null— never expose internal error details like “Connection string not found” or SQL errors

Registration in Program.cs

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddProblemDetails();builder.Services.AddExceptionHandler<GlobalExceptionHandler>();

var app = builder.Build();

app.UseExceptionHandler();

app.Run();- Line 3:

AddProblemDetails()registersIProblemDetailsServiceand related services. Without this, our handler can’t use the problem details service. - Line 4:

AddExceptionHandler<GlobalExceptionHandler>()registers our handler as a singleton in the DI container. - Line 8:

UseExceptionHandler()adds the exception handling middleware to the pipeline. This middleware catches exceptions and delegates to our registered handlers.

That’s it. Clean, maintainable, and production-ready.

What’s New in .NET 10: SuppressDiagnosticsCallback

.NET 10 introduces a significant change to how the exception handling middleware logs errors. Previously, in .NET 8 and 9, the middleware would always emit diagnostic logs (at Error level) for every exception — even if your IExceptionHandler already handled it.

This was annoying. You’d end up with duplicate logs: one from your handler and one from the middleware.

.NET 10 changes the default behavior: When your IExceptionHandler.TryHandleAsync returns true, the middleware no longer emits diagnostics by default. This makes more sense — if you handled the exception, you probably logged it yourself.

Controlling Diagnostic Output

If you need the old behavior or want fine-grained control, use SuppressDiagnosticsCallback:

// Revert to .NET 8/9 behavior - always emit diagnosticsapp.UseExceptionHandler(new ExceptionHandlerOptions{ SuppressDiagnosticsCallback = _ => false});

// Suppress diagnostics only for specific exception typesapp.UseExceptionHandler(new ExceptionHandlerOptions{ SuppressDiagnosticsCallback = context => context.Exception is NotFoundException or BadRequestException});Let me explain both scenarios:

Lines 1-5 (Revert to old behavior): The callback receives an ExceptionHandlerContext but we ignore it (using _) and always return false. Returning false means “don’t suppress diagnostics” — so the middleware will log every exception, just like .NET 8/9 did.

Lines 7-12 (Selective suppression): Here we check the exception type. If it’s a NotFoundException or BadRequestException, we return true (suppress diagnostics). For all other exceptions, we return false (emit diagnostics). This is useful when you want to log unexpected errors at the middleware level but skip logging for expected business errors that you’re already handling in your IExceptionHandler.

This is useful when:

- You have transient exceptions that don’t need to clutter your logs

- You want middleware-level logging for some exceptions but not others

- You’re migrating from .NET 9 and need consistent logging behavior during the transition

Chaining Multiple Exception Handlers

One of the most powerful features of IExceptionHandler is the ability to chain multiple handlers. Each handler can decide whether to handle the exception or pass it to the next one.

public sealed class NotFoundExceptionHandler(ILogger<NotFoundExceptionHandler> logger) : IExceptionHandler{ public async ValueTask<bool> TryHandleAsync( HttpContext httpContext, Exception exception, CancellationToken cancellationToken) { if (exception is not NotFoundException notFound) { return false; // Let the next handler try }

logger.LogWarning("Resource not found: {Message}", notFound.Message);

httpContext.Response.StatusCode = StatusCodes.Status404NotFound; await httpContext.Response.WriteAsJsonAsync(new ProblemDetails { Status = 404, Title = "Resource Not Found", Detail = notFound.Message }, cancellationToken);

return true; // We handled it }}Here’s the key pattern:

- Lines 8-10: The guard clause is the most important part. We check if the exception is

NotFoundException. If it’s NOT, we immediately returnfalse. This tells the middleware: “I can’t handle this, try the next handler.” - Line 13: We log at

Warninglevel, notError. A 404 isn’t an error in your system — it’s a valid response for a missing resource. This keeps your error logs clean. - Lines 15-21: We write the response directly using

WriteAsJsonAsync. Notice we pass thecancellationToken— always do this to support request cancellation. - Line 23: Returning

truetells the middleware: “I handled this, stop looking for other handlers.”

Here’s another handler for validation errors:

public sealed class ValidationExceptionHandler(ILogger<ValidationExceptionHandler> logger) : IExceptionHandler{ public async ValueTask<bool> TryHandleAsync( HttpContext httpContext, Exception exception, CancellationToken cancellationToken) { if (exception is not ValidationException validation) { return false; }

logger.LogWarning("Validation failed: {Message}", validation.Message);

httpContext.Response.StatusCode = StatusCodes.Status400BadRequest; await httpContext.Response.WriteAsJsonAsync(new ValidationProblemDetails { Status = 400, Title = "Validation Failed", Errors = validation.Errors }, cancellationToken);

return true; }}- Lines 8-10: Same pattern — check if it’s our exception type, return

falseif not. - Lines 16-20: We use

ValidationProblemDetailsinstead of regularProblemDetails. This subclass includes anErrorsdictionary that maps field names to error messages — perfect for form validation.

Registration Order Matters

builder.Services.AddExceptionHandler<NotFoundExceptionHandler>();builder.Services.AddExceptionHandler<ValidationExceptionHandler>();builder.Services.AddExceptionHandler<GlobalExceptionHandler>(); // FallbackThe handlers execute in registration order:

- Line 1:

NotFoundExceptionHandlerruns first. If the exception isNotFoundException, it handles it and returnstrue. Otherwise, returnsfalse. - Line 2:

ValidationExceptionHandlerruns next. Same pattern — handlesValidationExceptionor passes along. - Line 3:

GlobalExceptionHandleris the fallback. It should handle ALL exceptions (never returnfalse) because it’s the last line of defense.

This pattern keeps each handler focused on one exception type, making them easy to test and maintain. You can add or remove handlers without touching the others.

Silencing Built-in Middleware Logs

Even in .NET 10, you might want to silence the default logs from Microsoft.AspNetCore.Diagnostics.ExceptionHandlerMiddleware. Add this to your appsettings.json:

{ "Logging": { "LogLevel": { "Default": "Information", "Microsoft.AspNetCore": "Warning", "Microsoft.AspNetCore.Diagnostics.ExceptionHandlerMiddleware": "None" } }}Line 6 is the key. By setting the log level to None for the middleware’s specific namespace, you completely disable its logging output. The middleware still functions — it catches exceptions and calls your handlers — but it won’t write to your logs.

Why would you want this?

- Your

IExceptionHandleralready logs the exception with your preferred format and log level - You don’t want duplicate entries cluttering your observability platform

- You have specific logging requirements that the middleware doesn’t meet

This ensures you only see logs from your handlers, not duplicate middleware logs.

Complete Working Example

Let’s put it all together with a minimal, single-file example. This is great for learning and quick prototypes — you can copy-paste it into a new .NET 10 project and run it immediately. For production applications, see the Production-Ready Project Structure section below where we organize this into proper folders.

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Diagnostics;using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;using System.Net;

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddProblemDetails(options =>{ options.CustomizeProblemDetails = ctx => { ctx.ProblemDetails.Extensions["traceId"] = ctx.HttpContext.TraceIdentifier; ctx.ProblemDetails.Extensions["timestamp"] = DateTime.UtcNow; ctx.ProblemDetails.Instance = $"{ctx.HttpContext.Request.Method} {ctx.HttpContext.Request.Path}"; };});

builder.Services.AddExceptionHandler<GlobalExceptionHandler>();

builder.Services.AddOpenApi();

var app = builder.Build();

app.UseExceptionHandler();

app.MapOpenApi();

// Test endpointsapp.MapGet("/", () => "Global Exception Handling Demo - .NET 10");

app.MapGet("/products/{id:guid}", (Guid id) =>{ // Simulate not found throw new NotFoundException("Product", id);});

app.MapPost("/products", (ProductRequest request) =>{ if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(request.Name)) { throw new BadRequestException("Product name is required"); } return Results.Created($"/products/{Guid.NewGuid()}", request);});

app.MapGet("/error", () =>{ // Simulate unexpected error throw new InvalidOperationException("Something went terribly wrong!");});

app.Run();

// Records and Exceptionspublic record ProductRequest(string Name, decimal Price);

public abstract class AppException(string message, HttpStatusCode statusCode = HttpStatusCode.InternalServerError) : Exception(message){ public HttpStatusCode StatusCode { get; } = statusCode;}

public sealed class NotFoundException(string resourceName, object key) : AppException($"{resourceName} with identifier '{key}' was not found.", HttpStatusCode.NotFound);

public sealed class BadRequestException(string message) : AppException(message, HttpStatusCode.BadRequest);

// Exception Handlerpublic sealed class GlobalExceptionHandler( ILogger<GlobalExceptionHandler> logger, IProblemDetailsService problemDetailsService) : IExceptionHandler{ public async ValueTask<bool> TryHandleAsync( HttpContext httpContext, Exception exception, CancellationToken cancellationToken) { logger.LogError(exception, "Exception occurred. TraceId: {TraceId}", httpContext.TraceIdentifier);

var (statusCode, title) = exception switch { AppException appEx => ((int)appEx.StatusCode, appEx.Message), _ => (StatusCodes.Status500InternalServerError, "An unexpected error occurred") };

httpContext.Response.StatusCode = statusCode;

return await problemDetailsService.TryWriteAsync(new ProblemDetailsContext { HttpContext = httpContext, ProblemDetails = new ProblemDetails { Status = statusCode, Title = title } }); }}Code Walkthrough

Lines 7-15 (Global ProblemDetails Customization):

builder.Services.AddProblemDetails(options =>{ options.CustomizeProblemDetails = ctx => { ctx.ProblemDetails.Extensions["traceId"] = ctx.HttpContext.TraceIdentifier; ctx.ProblemDetails.Extensions["timestamp"] = DateTime.UtcNow; ctx.ProblemDetails.Instance = $"{ctx.HttpContext.Request.Method} {ctx.HttpContext.Request.Path}"; };});This configures all ProblemDetails responses globally — not just from our exception handler, but also from Results.Problem(), validation errors, and status code pages. Every error response will automatically include the trace ID, timestamp, and request path.

Line 17: Registers our exception handler. Remember, it’s a singleton — one instance handles all requests.

Line 23: Adds the exception handling middleware to the pipeline. This must come early — before your endpoints — so it can catch exceptions from anywhere downstream.

Lines 30-34 (Not Found Endpoint):

app.MapGet("/products/{id:guid}", (Guid id) =>{ throw new NotFoundException("Product", id);});This endpoint always throws NotFoundException. In a real app, you’d fetch from a database and throw only if the product doesn’t exist. The exception bubbles up, gets caught by our handler, and returns a 404 with proper ProblemDetails.

Lines 36-43 (Validation Example):

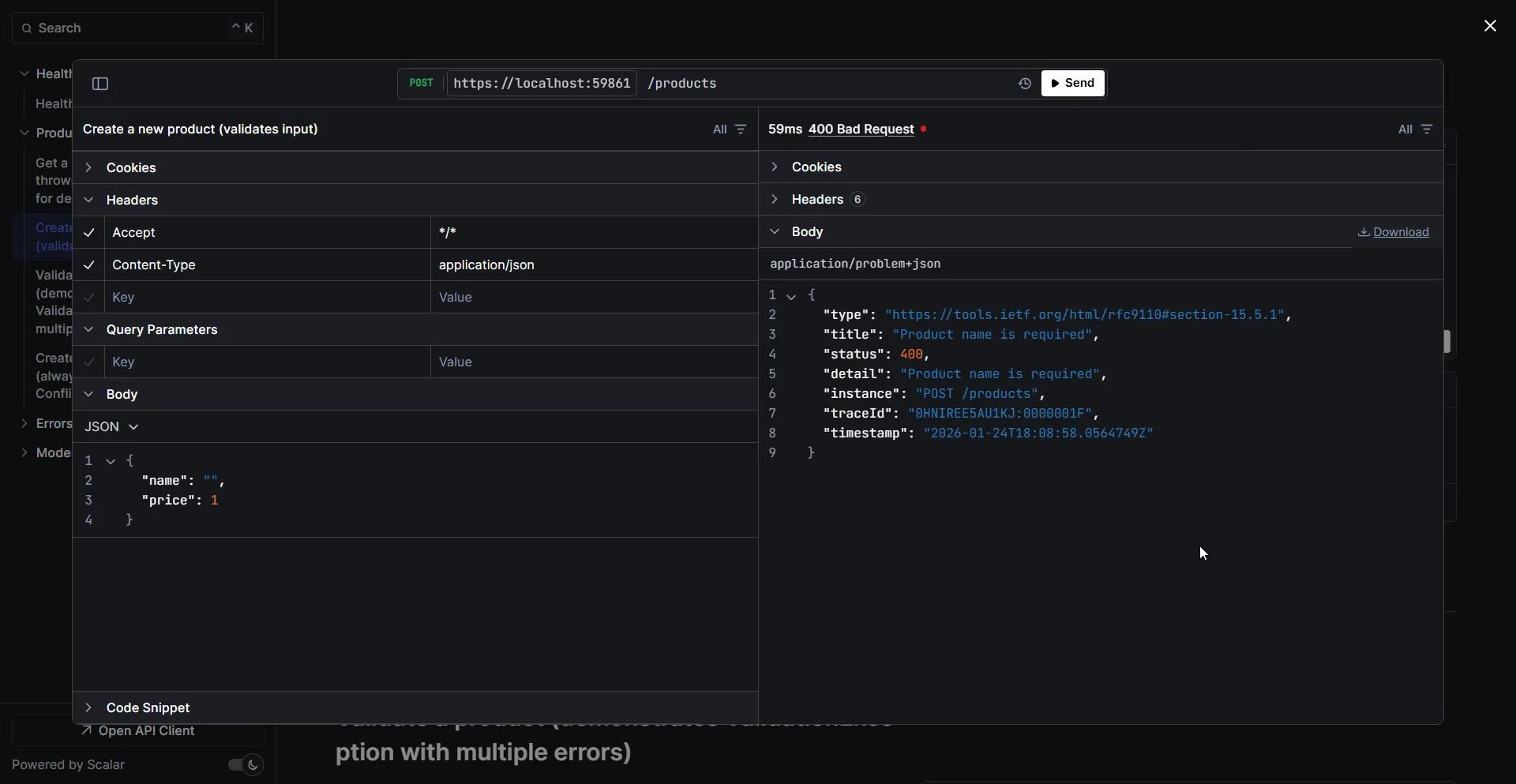

app.MapPost("/products", (ProductRequest request) =>{ if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(request.Name)) { throw new BadRequestException("Product name is required"); } return Results.Created($"/products/{Guid.NewGuid()}", request);});A simple validation — if the name is empty, throw BadRequestException. This returns a 400 with a clear error message.

Lines 45-49 (Unexpected Error):

app.MapGet("/error", () =>{ throw new InvalidOperationException("Something went terribly wrong!");});This simulates an unexpected error — something you didn’t anticipate. The handler catches it, returns 500, and does not expose the internal message in production.

When you call GET /products/{some-guid}, you’ll get:

{ "type": "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.5", "title": "Product with identifier 'some-guid' was not found.", "status": 404, "instance": "GET /products/some-guid", "traceId": "0HN123ABC:00000001", "timestamp": "2026-01-21T10:30:00.000Z"}Here’s what a validation error looks like in Scalar when you POST to /products with an empty name:

Isn’t that clean?

Production-Ready Project Structure

The single-file example above is great for learning, but in production you’ll want a proper folder structure. Here’s the recommended layout for organizing your exception handling code:

YourApi/├── Exceptions/│ ├── AppException.cs│ ├── NotFoundException.cs│ ├── BadRequestException.cs│ ├── ConflictException.cs│ └── ValidationException.cs├── Handlers/│ ├── GlobalExceptionHandler.cs│ ├── NotFoundExceptionHandler.cs # Optional - for handler chaining│ └── ValidationExceptionHandler.cs # Optional - for handler chaining├── Program.cs├── appsettings.json└── appsettings.Development.jsonException Classes in Separate Files

Each exception should live in its own file under the Exceptions/ folder. Here’s the production version using primary constructors:

Exceptions/AppException.cs

using System.Net;

namespace YourApi.Exceptions;

public abstract class AppException(string message, HttpStatusCode statusCode = HttpStatusCode.InternalServerError) : Exception(message){ public HttpStatusCode StatusCode { get; } = statusCode;}Exceptions/NotFoundException.cs

using System.Net;

namespace YourApi.Exceptions;

public sealed class NotFoundException(string resourceName, object key) : AppException($"{resourceName} with identifier '{key}' was not found.", HttpStatusCode.NotFound);Exceptions/BadRequestException.cs

using System.Net;

namespace YourApi.Exceptions;

public sealed class BadRequestException(string message) : AppException(message, HttpStatusCode.BadRequest);Exceptions/ConflictException.cs

using System.Net;

namespace YourApi.Exceptions;

public sealed class ConflictException(string message) : AppException(message, HttpStatusCode.Conflict);Exceptions/ValidationException.cs

using System.Net;

namespace YourApi.Exceptions;

public sealed class ValidationException : AppException{ public IDictionary<string, string[]> Errors { get; }

public ValidationException(IDictionary<string, string[]> errors) : base("One or more validation errors occurred.", HttpStatusCode.BadRequest) { Errors = errors; }

public ValidationException(string field, string error) : base("One or more validation errors occurred.", HttpStatusCode.BadRequest) { Errors = new Dictionary<string, string[]> { { field, [error] } }; }}Full GlobalExceptionHandler Implementation

Here’s the production-ready handler with all helper methods in its own file:

Handlers/GlobalExceptionHandler.cs

using YourApi.Exceptions;using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Diagnostics;using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

namespace YourApi.Handlers;

public sealed class GlobalExceptionHandler( ILogger<GlobalExceptionHandler> logger, IProblemDetailsService problemDetailsService) : IExceptionHandler{ public async ValueTask<bool> TryHandleAsync( HttpContext httpContext, Exception exception, CancellationToken cancellationToken) { logger.LogError(exception, "Unhandled exception occurred. TraceId: {TraceId}", httpContext.TraceIdentifier);

var (statusCode, title) = MapException(exception);

httpContext.Response.StatusCode = statusCode;

var problemDetails = new ProblemDetails { Status = statusCode, Title = title, Type = GetProblemType(statusCode), Instance = httpContext.Request.Path, Detail = GetSafeErrorMessage(exception, httpContext) };

problemDetails.Extensions["traceId"] = httpContext.TraceIdentifier; problemDetails.Extensions["timestamp"] = DateTime.UtcNow;

return await problemDetailsService.TryWriteAsync(new ProblemDetailsContext { HttpContext = httpContext, ProblemDetails = problemDetails }); }

private static (int StatusCode, string Title) MapException(Exception exception) => exception switch { AppException appEx => ((int)appEx.StatusCode, appEx.Message), ArgumentNullException => (StatusCodes.Status400BadRequest, "Invalid argument provided"), ArgumentException => (StatusCodes.Status400BadRequest, "Invalid argument provided"), UnauthorizedAccessException => (StatusCodes.Status401Unauthorized, "Unauthorized"), _ => (StatusCodes.Status500InternalServerError, "An unexpected error occurred") };

private static string GetProblemType(int statusCode) => statusCode switch { 400 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.1", 401 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.2", 403 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.4", 404 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.5", 409 => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.5.10", _ => "https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9110#section-15.6.1" };

private static string? GetSafeErrorMessage(Exception exception, HttpContext context) { var env = context.RequestServices.GetRequiredService<IHostEnvironment>(); if (env.IsDevelopment()) { return exception.Message; } return exception is AppException ? exception.Message : null; }}Clean Program.cs

With the handlers in separate files, your Program.cs stays clean and focused:

using YourApi.Handlers;using Scalar.AspNetCore;

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddProblemDetails(options =>{ options.CustomizeProblemDetails = ctx => { ctx.ProblemDetails.Extensions["traceId"] = ctx.HttpContext.TraceIdentifier; ctx.ProblemDetails.Extensions["timestamp"] = DateTime.UtcNow; ctx.ProblemDetails.Instance = $"{ctx.HttpContext.Request.Method} {ctx.HttpContext.Request.Path}"; };});

// Register exception handlers (order matters for chaining)builder.Services.AddExceptionHandler<GlobalExceptionHandler>();

builder.Services.AddOpenApi();

var app = builder.Build();

app.UseExceptionHandler();

app.MapOpenApi();app.MapScalarApiReference(); // API docs at /scalar/v1

// Your endpoints here...

app.Run();Note: We’re using Scalar for API documentation instead of Swagger. It’s cleaner, faster, and works great with .NET 10’s built-in OpenAPI support.

Get the Complete Sample Code

The full production-ready sample with all exception types, handlers, and test endpoints is available on GitHub:

👉 Download the complete source code

Clone it and run it locally:

git clone https://github.com/codewithmukesh/dotnet-webapi-zero-to-hero-course.gitcd dotnet-webapi-zero-to-hero-course/modules/01-getting-started/global-exception-handlingdotnet run --project GlobalExceptionHandling.ApiThen navigate to http://localhost:5000/scalar/v1 to explore the API and test the exception handling endpoints.

Performance Consideration: The Result Pattern

I should mention this because exceptions aren’t free. As David Fowler (Microsoft’s ASP.NET Core architect) points out, exceptions are expensive in terms of performance. They involve stack unwinding, memory allocation, and can significantly impact throughput under load.

For expected error conditions (like validation failures or not-found scenarios), consider using the Result pattern instead:

public record Result<T>{ public T? Value { get; init; } public string? Error { get; init; } public bool IsSuccess => Error is null;

public static Result<T> Success(T value) => new() { Value = value }; public static Result<T> Failure(string error) => new() { Error = error };}

// Usagepublic Result<Product> GetById(Guid id){ var product = _repository.Find(id); return product is not null ? Result<Product>.Success(product) : Result<Product>.Failure($"Product {id} not found");}Let me break this down:

- Lines 1-9 (Result Record): This is a simple discriminated union. A

Result<T>either has aValue(success) or anErrormessage (failure), never both. TheIsSuccessproperty checks if there’s no error. - Line 7: Factory method for successful results — wraps the value.

- Line 8: Factory method for failures — stores the error message.

- Lines 12-18 (Usage): Instead of throwing

NotFoundException, we returnResult<Product>.Failure(...). The caller checksIsSuccessand handles accordingly.

The advantage? No stack unwinding, no expensive exception objects. Just a simple record allocation. Under high load, this can make a noticeable difference.

In your endpoint, you’d handle it like this:

app.MapGet("/products/{id:guid}", (Guid id, ProductService service) =>{ var result = service.GetById(id); return result.IsSuccess ? Results.Ok(result.Value) : Results.NotFound(result.Error);});Use exceptions for truly exceptional situations — things that shouldn’t happen during normal operation (database connection lost, file system errors, external service failures). Use the Result pattern for expected business failures (not found, validation errors, insufficient permissions).

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I use IExceptionHandler or custom middleware?

Use IExceptionHandler if you're on .NET 8 or later. It's the recommended approach by Microsoft, integrates with the built-in middleware, and is easier to test. Only use custom middleware if you're stuck on .NET 7 or earlier.

Can I use multiple IExceptionHandler implementations?

Yes. Register them in the order you want them executed. Each handler can return false to pass the exception to the next handler in the chain.

Should I expose exception details to clients?

Never in production. Stack traces and internal error messages can expose security vulnerabilities. Only expose safe, user-friendly messages. In development, you can show more details for debugging.

What's the difference between IExceptionHandler and ExceptionFilterAttribute?

ExceptionFilterAttribute only works within the MVC pipeline (controllers). IExceptionHandler works for the entire ASP.NET Core pipeline, including minimal APIs, middleware, and controllers.

How do I handle validation errors separately?

Create a dedicated ValidationExceptionHandler and register it before your global handler. Return false from handlers that don't match the exception type.

What changed in .NET 10 for exception handling?

The main change is SuppressDiagnosticsCallback on ExceptionHandlerOptions. By default, .NET 10 no longer emits diagnostic logs when your handler returns true. This prevents duplicate logging.

Summary

Global exception handling is essential for building robust ASP.NET Core applications. Here’s what we covered:

- Try-catch blocks are not suitable for global handling — too repetitive and inconsistent

- Custom middleware works but is now outdated for .NET 8+ projects

IExceptionHandleris the modern, recommended approach — clean, testable, and chainable- .NET 10 introduces

SuppressDiagnosticsCallbackto control diagnostic output - Use

IProblemDetailsServicefor RFC 9457-compliant error responses - Chain multiple handlers for different exception types

- Consider the Result pattern for expected failures to avoid performance overhead

- Organize your code with a proper folder structure for production applications

👉 Get the complete source code on GitHub — clone it, run it, and use it as a starting point for your projects.

If you found this guide helpful, share it with your team. Building consistent error handling from day one saves countless debugging hours down the road.

Happy Coding :)